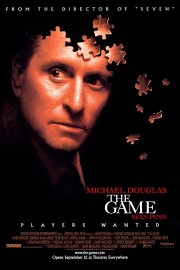

The Game

In some ways, it feels like it took David Fincher a while to get revved up as a director, moving away from pulp dramas to more “prestige” films such as “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button,” “The Social Network,” and “The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo,” all of which were nominated for major awards, including several Oscars. However, when looking at his filmmography closely, every film he’s made, from the much-maligned “Alien 3” to “Fight Club” to “Dragon Tattoo,” seems to tie into the other, be it in visual style or narrative threads.

Even when one looks at his career in the latter sense, his 1997 thriller, “The Game,” has always seemed like a black sheep entry in his overall filmmography. It was his first film since his 1995 film, “Se7en,” thrust him into the spotlight as a director, and won the Best Movie award at the MTV Movie Awards. Some people didn’t like it, understandably so, but for others like myself, it sucked us in, and didn’t let go. Like “Se7en,” it’s only increased in stature over the years, and earlier this year, it was released by The Criterion Collection in a widely acclaimed new edition.

After 16 years, the story of “The Game” is well-known. The movie stars Michael Douglas as Nicholas Van Orton, an investment banker who lives and breathes his job, and has no real need for personal connections. It’s his 48th birthday, and he is having flashes and memories of his father, a successful man in his own right, who killed himself on his 48th birthday, which Nicholas witnessed. His brother, Conrad (Sean Penn), wants to have lunch, and reluctantly, Nicholas agrees. Conrad has a present for him– a certificate for a company called CRS, which runs a virtual reality game that involves, well, different things for different people. Nicholas is intrigued, so he visits CRS, and spends his entire day doing tests that will help tailor the game to the participant. The next day, he gets a call saying that he didn’t fit the profile for the game, and wishing him well. When he gets home that night, he finds a wooden clown in his driveway, in the same place his father was when he died. Let the games begin.

On the one hand, I can understand where people like Leonard Maltin are coming from when they call “The Game” “unusually mean-spirited,” but really, were people expecting something uplifting from the director of the pitch-black “Se7en?” Watching the film in light of Fincher’s follow-up, “Fight Club,” the screenplay by John Brancato and Michael Ferris, with uncredited work by “Se7en” scribe Andrew Kevin Walker, ties in nicely with that film’s surreal notions of taking pain and fear, and turning it into the sensation of feeling alive. Yes, happens to Van Orton in the movie is cruel, and is right on the edge of legality, but the point is to make this shell of a man, who has no issues with going into a long-time family friend’s office, and firing him when his company doesn’t perform up to snuff, feeling something, regardless of how those feelings are elicited.

Seeing this film for the first time since 1997, I was absolutely riveted from start to finish, arguably, more so than I was when I watched it in theatres. That was the case even though I knew the ending, which has been a sore spot for even some of the film’s supporters over the years. That says a lot about not only the work Fincher and his collaborators do (especially cinematographer Harris Savides and composer Howard Shore), but also the actors, starting with Douglas, who’s done this type of nervous, anxiety-provoked character before in films like “Disclosure,” “Basic Instinct” (also set in San Francisco), and “Fatal Attraction.” This is probably his best role of the bunch, one where he truly puts himself in other people’s hands, and gives a fearless performance. In the other key roles, Penn is superb at playing both cool and collected during his first scene with Douglas, and paranoid and anxious in his second one, while Deborah Kara Unger plays Christine, a waitress that finds herself in the middle of things with Nicholas.

In the end, this is all Fincher’s film, from start to finish, and watching it again, I find it very much at home in his filmmography, and not just because of its gritty, unnerving style. The film is all about a life-transforming moment, which will have reverberations throughout the rest of our life, just like the one the Narrator has in “Fight Club”; Robert Graysmith has in “Zodiac” (Fincher’s best film); and Mark Zuckerberg has in “The Social Network.” In this one, the stakes are higher, but the rewards are invariably greater, and Nicholas takes advantage of them when all is said and done. And after this film, Fincher found the freedom to explore things that interested him completely as a filmmaker, and audiences have reaped the benefits.