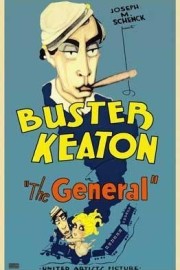

The General

There are three major classic films set during the Civil War- “Birth of a Nation,” “Gone With the Wind,” and Buster Keaton’s “The General.” While in execution they couldn’t be more different, they have one similarity- the North is the aggressor, disturbing the peace, lives and loves of the South’s inhabitants. Only in Griffith’s flawed work are the politics that lead to the War acknowledged, but it was watching “The General” again that this odd coincidence came up, so I thought it was worth mentioning.

It’s by sheer coincidence, also, that I screened Keaton’s “Sherlock Jr.” for several of my friends last week for my birthday. That surreal gem is my favorite film of all-time. But “The General” sucked me in, and allowed me to rediscover its’ own greatness anew.

A lot of that has to be in the context of how I watched it. I had the great pleasure of watching it at the Fabulous Fox Theatre in Atlanta, where renowned organist Clark Wilson played along on the “Mighty Mo” organ at the theatre, allowing me my first opportunity to watch a silent film as it was originally shown- with live music accompanying the film itself. It was truly among my most delightful experiences of all-time.

The film is one of the last silent masterpieces- the same year it was released “The Jazz Singer” introduced pre-recorded sound to the cinema, signaling an end to the silent era. But watching this film, it’s impossible to imagine it with dialogue not on title cards- the pacing would suffer, and if there’s one thing Keaton understood instinctively about silent cinema, it was that in the absence of dialogue, execution was everything. That’s why his films still stand as perhaps the greatest of that era.

Keaton took the story of “The General” from the true story of Union spies who hijacked a Confederate train in an attempt to cut off Southern supply routes. In Keaton’s version, they do more than that- they take away the two great loves of Johnnie Gray’s life- his engine, and Annabelle Lee (Marion Mack). When the war first broke out, he tried to enlist, but as an engineer was too valuable to the cause, and he wasn’t accepted. Not that anyone bothered to tell him that, and when Annabelle finds out he isn’t a man in uniform, she doesn’t want him in her life. But fate has a tricky way of doubling back on these two, when Annabelle is caught on the General when the Union steals it, and Johnnie gives chase on the Texas.

Keaton’s imagination is in full-form here, as he finds ingenious ways to make this chase between two trains funny, exciting, and original. The way Johnnie using the canon against the Union soldiers seems to backfire…until a fortunate turn in the tracks sends it on its’ proper way. The way Johnnie gets rid of a couple of kids who’ve followed him on his way to call on Annabelle. The ways he tries to get his enlistment papers, and the difficulties he has in getting wood for the steam engine. Trying to get back on the General when Annabelle can’t stop the train, and what happens when she figures out how to put it in reserve. At these and many other moments, the audience laughed and applauded in a way I haven’t experienced in a movie theatre in many a year.

Keaton is known as a master of comedy, but “The General” is more than that. It’s an attempt to tell a story that’s ambitious but entertaining on all levels. Whether you’re talking about “Sherlock Jr.” or “The Cameraman” or “Our Hospitality” of “The General,” laughs were important to Keaton, but not as much as making the audience feel…something. Love, hate, laughs, sadness, triumph, agony. He may have been a comedian first, but at his finest, he was a storyteller. Watching it with a packed crowd Tuesday night, with an organ providing the fitting accompaniment, he showed why he’s one of the best of both we’ve ever seen.