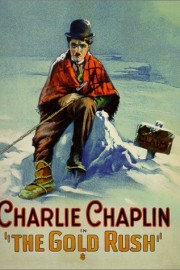

The Gold Rush

While I’m definitely more in the Buster Keaton camp in the eternal Keaton-Chaplin debate, there’s something about the lovely sentimentality in Charlie Chaplin’s films that is exquisite and unforgettable. I identify much more with Keaton’s characters overall, but the hopeless romantic in Chaplin’s Little Tramp is much closer to how I feel when it comes to love. This was never truer than it was in his beloved “City Lights,” where the Tramp falls in love with a blind girl, who cannot see him for his outer demeanor, but sees who he is on the inside, leading to the famous moment where, after she’s gotten her sight back, she doesn’t recognize him until their hands touch, and the rest is cinematic history.

His 1925 film, “The Gold Rush,” is the closest of his great classics in tone to “City Lights,” and I think that’s because it was a pure silent film. Well, it originally was– the only version I’ve ever seen is one Chaplin re-cut later, with narration, written and recorded by Chaplin himself, replacing the title cards. Because it was done by Chaplin, that allows the film to maintain the authenticity of the original classic while also being a little bit more accessible to audiences who may not have any interest in silent films otherwise. Silent comedy has a way of engaging the modern audience in a way other silent genres can’t really do, though, and both Chaplin and Keaton were masters in their field.

This film casts the Little Tramp as a gold prospector, who has made his way into the hills during the great gold rush of the 19th century. He finds himself in a cabin with Big Jim McKay (Mack Swain), and they become friends (or, at least, allies), and search together, although a third prospector (Black Larsen, played by Tom Murray) comes up on them, and wants them out. They manage to get Larsen out of the cabin, but after a while, delirium takes over the Tramp and Big Jim, and they’re eating shoes, and eventually, picturing the other as food. Big Jim hits it big, though, and hides his findings before setting out to try and find more, leaving the Tramp behind. Eventually, a town builds up around where the Tramp is, and there he meets Georgia (Georgia Hale), and while she hangs out with a playboy, she asks the Tramp to dance to make the playboy jealous, and there is where another of Chaplin’s iconic love stories plays out before the Tramp and Big Jim reunite, and find themselves rich.

The thing about Chaplin’s films that makes them stand out, and apart, from Keaton’s work is how carefully calibrated the emotional aspects are. Keaton was meticulous when it came to staging his set pieces, centering more on the comedy than the story, at times, but Chaplin managed to meld the two almost effortlessly. Think about the moment when the Tramp does the dinner roll dance for Georgia and her friends as an expression of his feelings: as comedy, it’s an amusing and simple piece, but as an emotional moment, we feel the affection he has for Georgia in the act. And there’s a clever piece of physical comedy wherein the Tramp’s pants are falling down during a dance with Georgia. He finds a rope to tie around his waist, but it’s attached to a dog, who follows him around the dance floor. Chaplin was inventive in his brand of comedy in a different way from Keaton, and it’s something that makes his films memorable works of art. He plays for the heart, isn’t ashamed of it, and he nails it. He wasn’t the most recognizable person in early cinema for nothing, and almost a century later, his imprint remains indelible.