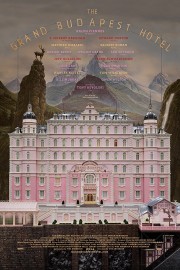

The Grand Budapest Hotel

While watching “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” I couldn’t help but think of all of Wes Anderson’s films existing within the same universe. (Even the delightful stop motion creation, “Fantastic Mr. Fox.”) Anderson has used the past two decades creating a singular vision of the world that is at once precise, loopy, evocative of the past, while also seeming to be ahead of their time aesthetically. He may never win an Oscar– though hopefully, he’ll be a winner for writing at least one day –but he’s concocting such a unique body of work that in the end, it’ll never be forgotten. However, while this was the first of his films I thought might hold something of a key to a unified Anderson universe, wherein the Tenenbaum family and Max Fischer and Gustave H. and the brother criminals of “Bottle Rocket” coexist, it wasn’t until “Grand Budapest Hotel” that I thought there was such a cohesiveness between all of Anderson’s movies.

Of course, that’s merely critical speculation, and not really useful as critical thinking about this or any of Anderson’s films– I point to it only to acknowledge the precise synchronicity that exists within all of Anderson’s movies, which seemed to crystallize in “The Grand Budapest Hotel.” My two favorite films of Anderson’s remain “Moonrise Kingdom” and the criminally underrated “The Darjeeling Limited,” which represent the most mature storytelling of the director’s career, but it’s impossible for any fan of the filmmaker’s not to get positively drunk on the lovely, odd, and emotional work Anderson does here. The film runs a tad long, but it’s too fun to be dismissed, and fits in wonderfully with second-tier efforts like “Fantastic Mr. Fox,” “The Royal Tenenbaums,” and “Rushmore.”

The main source of enjoyment, for myself and others, comes from the excellent, hilariously straight-faced performance by Ralph Fiennes as Gustave H., the concierge at the titular hotel during the ’30s before war ravaged the land. Fiennes is not the first actor you would think of when it comes to comedy, but with a script as juicy as the one Anderson and co-writer Hugo Guinness provide, Fiennes is an inspired choice to play a consummate professional, always attentive to his guest’s needs, even when those guests needs are more…intimate in nature. One of those guests is Madame D., an elderly matron played by the unrecognizable Tilda Swinton, whom Gustave deeply loves, and has that love reciprocated. Shortly after she leaves the hotel, she dies, and that’s when things become difficult for Gustave, who is not only left a priceless piece of art in her will after a late, unconfirmed amendment, but is also implicated in her death. It’s not enough that one must grieve for the deceased? For Gustave, he has to confirm his innocence, as well?

Gustave is not the one relaying the story, however; that honor goes to his young lobby boy, Zero, played by Tony Revolori in one of the most amazing breakthrough performances in all of Anderson’s films, which is saying something considering the young leads from “Moonrise Kingdom.” Zero becomes Gustave’s shadow, his partner in crime at times, and a loyal friend, so much so that Gustave, upon his death, leaves the Grand Budapest to Zero. It’s the adult Zero (F. Murray Abraham, a delight), still operating the Grand Budapest (and vastly wealthy), telling the story to an author (Jude Law) who then writes a book about the tale. The author (now played by Tom Wilkinson), who seems to be appearing in either a television interview, or an instructional film for young writers, is the one who bookends the film, and his affection for the story mirrors Anderson’s, leaving me to think the writer is the director’s onscreen surrogate.

But it’s the tale of Gustave and Zero’s misadventures that make the spine of the film– like the use of Bob Ballaban in “Moonrise Kingdom,” the layers-of-an-onion storytelling device Anderson uses is intended to create a heightened reality in which the film exists, not that it needs it with the exacting, offbeat visual style Anderson creates. As always, the cinematography by Robert Yeoman; the production design; and the costume design give the illusion of reality, but feel just a bit off from it. This movie seems like it could exist in the real world, but it’s slightly removed from it, a feel highlighted in the lovely, quirky strains of Alexandre Desplat’s score, his third straight triumph with Anderson after “Fantastic Mr. Fox” and “Moonrise Kingdom.” And all of these elements work only to serve the story in all it’s strange, eccentric quality, played to effortly by a supporting cast that includes Bill Murray, Edward Norton, Harvey Keitel, Saoirse Ronan, Jason Schwartzman, Adrian Brody, Willem Dafoe, and Jeff Goldblum in small and vital roles around Fiennes and Revolori, who provide “Grand Budapest” with a heart and soul that has become more pronounced in Anderson’s films over the years, resulting in cinematic experiences as enlightening about the humanity as they are entertaining.