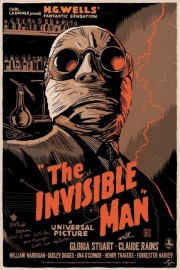

The Invisible Man

“The Invisible Man” isn’t a horror movie in the typical sense that we see in Universal’s horror slate from the ’30s to the ’50s as it is a psychological thriller. Even that isn’t really an effective description of the film, though, because a psychological thriller implies some sense of conflict in the main character, and Claude Rains’s title character doesn’t really have any conflict in his actions. When we meet him, he has already become invisible after the wrong concoctions of chemicals while working on an experiment. Now, he has come to a hotel in an isolated village to try and figure out how to reverse the process. He’s not above some mischief, though, and the longer things go, the more you get the sense that he’s losing his grip on reality, and his morality.

Adapting the novel by H.G. Wells is credited screenwriter R.C. Sherriff and director James Whale. Whale, as you surely know, is the director behind both “Frankenstein” and it’s superior sequel, “The Bride of Frankenstein.” While this film doesn’t feel quite as personal to the director as his “Frankenstein” movies were, it is no less entertaining a work of Gothic horror made within the studio system. It doesn’t have the striking production design of “Bride of Frankenstein” and “Dracula,” but it offers an unforgettable image of the Invisible Man himself, wearing a fedora, sunglasses, a trenchcoat, and bandages to hide the terrible fate that befell him. This is very much a case of the clothes making the man, and it makes for a disturbing movie monster that is the equal of Dracula, Frankenstein’s Monster and Lon Chaney’s Wolf Man in the pantheon of Universal’s monster movies. Add to that the voice of Claude Rains, which is capable of both engaging wit (as is best exemplified in “Casablanca”) and dramatic weight and danger, a quality that serves this character well, especially when he must abandon the old hotel and go to a friend’s house to lay low after assaulting the hotel owner’s wife. We don’t see Rains until the final scenes, when he is dying, but his presence as an actor is essential to bringing the character to life, and it’s one of the best performances I’ve seen in the Universal horror movies I’ve watched.

One of the things that makes Universal’s horror films from this era so easy to appreciate are the brisk running times- the longest one I’ve seen of the major ones runs at a scant 85 minutes (“Dracula”). That is certainly a blessing at a time when the average movie feels between 110 minutes and two hours, but it also feels like a hindrance to the filmmakers. Was this a studio-mandated choice, or did the filmmakers simply tell the story they wanted to tell in short order? I’m sure some research into the subject would answer the question for me, but it’s interesting that even someone like Whale, who I’m sure had plenty of freedom to do what he liked after the success of “Frankenstein” (and cashed it in big time on “Bride of Frankenstein”) still kept things short on his later films for the studio. A blessing of this is that there’s no needless subplots or over-complication of the narrative, but at the same time, it feels like we’re watching a film with no meat on it’s bones rather than a story fleshed-out as it probably could have been. That’s my issue with most of the Universal horror films from this era, with the exception of “Bride.” Though they’re well-made films and tell compelling horror stories, it feels like they are just products coming from a factory mentality rather than the passions of their creators. That doesn’t make them any less iconic in the history of horror cinema, however, and in “The Invisible Man,” that iconography is a haunting look at a man unhinged, slowly descending into madness, and it is extraordinary to watch.