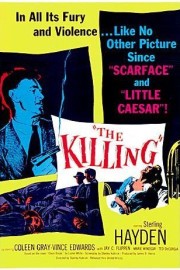

The Killing

Before Stanley Kubrick became a legendary filmmaker on the heels of films like “Paths of Glory,” “Spartacus,” “Lolita,” “Dr. Strangelove” and “2001: A Space Odyssey,” he was a director of crime dramas and film noirs. You won’t find the iconoclastic visionary he became in those early films, but rather, a photographer who took his unique eye to filmmaking, and developed his storytelling talents through genre productions. Some of his early films were documentary shorts, which I have not seen, but it’s fitting since in his greatest films, he seemed less interested in emotional stories and more in presenting bold cinematic worlds with an unbiased eye. His crime films (the only one of which I have not seen remains his debut, “Fear and Desire”) are where he honed his ability to tell a story, and with his last of those three films, “The Killing,” he best points to the master he would become when he combined his objectivity with his narrative interests. “2001” or “Strangelove” it is not, but it’s a successful heist thriller about a heist that goes according to plan until it doesn’t. It’s confident, ingenious in it’s construction, and grabs you during all of it’s 84-minute running time.

In “The Killing,” Kubrick and Jim Thompson (who wrote the dialogue; I’m guessing that means the narration) are adapting a novel by Lionel White about an elaborate heist at a racetrack. The job is headed by a career criminal named Johnny Clay (Sterling Hayden), who gets two-bit criminals (a couple of whom work at the track) to help pull off the robbery of over two million dollars at a racetrack. He has everything planned to the second: he has a long-range shooter who will cause a diversion by wounding one of the horses during the big race; a corrupt cop who will help with the getaway; a drunk who will cause distractions within the building, and a muscleman who will fight with security, giving Clay a chance get in and get the money. Kubrick shows the day of the heist from several different vantage points, bringing to mind Kurosawa’s “Rashomon,” but this isn’t a matter of the story getting more complicated from each perspective, but as a way of building tension, and showing us how it works. It does work, but before the day, we see the seeds that will cause things to go awry when we see a cashier at the track’s wife is involved in an affair, and wants their share for herself, whatever the cost. It’ll cost someone dearly, and in fact, no one really comes out ahead in the end, in what may be one of the most karmic endings in all of Kubrick’s career.

It’s striking to think of an upper-level Kubrick film that clocks in under two hours long, let alone under 90 minutes. (Kubrick is best when he lets his film’s breathe from a narrative standpoint, not including the short and brilliant “Dr. Strangelove.”) But strangely enough, “The Killing” feels very much like a full-bodied piece of Kubrick storytelling, if not in theme, then assuredly in it’s ability to look at it’s story with depth and focus. Visually, he was still working within the confines of film noir dramatic compositions rather than the singular camera angles that would define his best work. Though all of the performances are quite good, we don’t have one that stands out over the others, although the look of disbelief on Hayden’s face at the end is a thing of haunting beauty. What carries “The Killing” to the heights of some of the best crime dramas is how clear-eyed Kubrick presents the story while also adding complexity and a sophisticated storytelling approach to the proceedings. He may have been a genre director at the time, but we are watching the development of a great talent before our eyes watching this film. That’s not the only exciting thing Kubrick had to offer here.