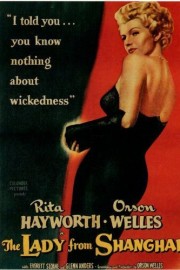

The Lady From Shanghai

It’s perhaps not surprising that Orson Welles directed two of the most unusual, and fascinating, tales in the annals of film noir, that quintessential American genre of crime, dangerous women, and questionable morality. The most well known is his 1958 masterpiece, “Touch of Evil,” but I would make the argument for his 1948 thriller, “The Lady From Shanghai,” being placed in the same company. (One can also claim a place for his great Kafka adaptation, “The Trial,” as well.) Watching “Shanghai” again, “Touch of Evil” is clearly the winner, but “Shanghai” is, if nothing else, a neglected gem from the great filmmaker.

After “Citizen Kane,” Welles famously lost all of the control he was allowed by studios, resulting in deep cuts to not just his next film, “The Magnificent Ambersons,” but to every other film he ever made for the studio system. Released seven years after “Kane,” “Shanghai” suffered the same fate, even though the film starred Columbia’s biggest star, Rita Hayworth, who was married to (and would soon be divorced from) Welles at the time. Something the cuts the studio couldn’t remove from this, or any other film Welles made, was the bold visual, and narrative, experimentation the director employed in telling the story.

Adapted from a novel by Sherwood King, Welles stars as Michael O’Hara, an Irish shipman who is walking through Central Park one night when he lays eyes on Elsa Bannister, played by Hayworth. It’s love (or at least, lust) at first sight, and his gaze doesn’t diminish even after he learns that she is married to a wealthy cripple, played by Everett Sloane. Not long after, he is sailing off with the Bannisters and their “friends,” which makes it difficult for him to indulge in his desires for Elsa. One of these friends is the eccentric George Grisby (Glenn Anders), who offers Michael a fascinating proposition.

At that point, the story goes into familiar noir territory of complications on top of complications when Grisby turns up dead, with O’Hara set up to take the fall. We know O’Hara didn’t do it, but the evidence isn’t in his favor, especially when the aspects of O’Hara and Elsa’s flirtation come out in the courtroom. But while the trial scene has some interest, the film really comes to life in the end, when O’Hara has escaped jail, and is hiding out in Chinatown with Elsa. They end up in an amusement park, climaxing in a visually thrilling scene in a hall of mirrors where Elsa and her husband are facing off. It’s one of the most exciting moments of Welles’s directing career, and proof that even though he lost the freedom to say what he wanted after “Kane,” he never lost the drive to give us images, reflective of what his characters had going on in their heads, that we would remember long after the film ended.

Thank you for this review. I used it in my reseach paper. 🙂