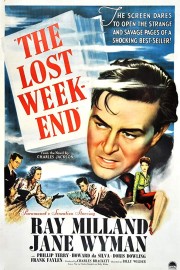

The Lost Weekend

“The Lost Weekend” was the start of a new era for alcoholism in cinema. Prior to Billy Wilder’s Oscar-winning film, drinking was treated as an every day thing for characters, and alcoholics were characterized as “fun drunks.” Based on the novel by Charles R. Jackson, and adapted by Wilder and Charles Brackett, “The Lost Weekend” introduced the tragic drunk that we would see evolve in films such as “The Days of Wine and Roses” and “Leaving Las Vegas.” Wilder’s film feels more melodramatic than those do, but it still retains a striking power, as a wannabe writer spends a weekend with the bottle, and is determined to live this life, even if it kills him.

Ray Milland won an Oscar for the role of Don Birnam, and we first see him in a New York apartment, getting ready for a weekend with his brother, Wick (Philip Terry), and one noticeable detail we see in the shot leading through the window into the apartment is a bottle hanging out of the window. Don’s girlfriend, Helen St. James (Jane Wyman), comes to see them off, with an offer of concert tickets she hopes her and Don can go to together. When Don suggests her and Wick go together, and he’ll take a later train, they both get suspicious; they are aware of Don’s drinking, and when Wick finds the bottle outside the window, they are on high alert. They leave anyway, after having poured the remaining bottle down the drain. But an addict will always find a way to get his fix, and when Don finds some money hidden in the apartment, he has the means to start his weekend alone.

Billy Wilder doesn’t go for broad stereotypes or characterizations in this film; it hits a lot of (now) predictable narrative beats- including a prolonged flashback where Don describes his first meeting with Helen, and how she came to know of his drinking, as well as some melodramatic flourishes in performances, but it doesn’t feel inauthentic in its representation of alcoholism. Milland is haunting to watch in this film, and we see the progressions in his despair, along with his frustration when people try and stop him from drinking, in a way that is frightening to watch. There are characters that move in and out of the narrative, so it is, largely, a one-man show for Milland, but he does have an amazing compliment in composer Miklos Rosza’s score, which was one of the first to incorporate the theremin, and that striking sound adds tremendous weight and energy to Don’s downward spiral.

Prior to “The Lost Weekend,” Wilder made the film noir classic, “Double Indemnity,” and after “Weekend” came “Sunset Boulevard.” All three films look at broken men who bring ruin to themselves by key decisions they make in their stories, whether it comes from drinking like it does for Milland in “Lost Weekend,” lust, which is Fred MacMurray’s downfall in “Double Indemnity,” and the dreams of fame laid out by a faded silent film star for William Holden in “Sunset Boulevard.” In terms of narrative, only “Indemnity” fits our traditional definition of film noir, but with these three films, Wilder expanded the idea of what that genre represented beyond simply being about crime. Film noir is a genre where the protagonists can be taken down a rabbit hole of painful emotions, from which there is very little way out. Don Birnam is the luckiest of Wilder’s protagonists in these three films- someone cares enough about him to give him a glimmer of hope, by the end. That feels like a false note for this film, but as cynical as Wilder was in his cinema, he wasn’t afraid of giving his protagonists a happy ending, if he felt as though they had earned it. Hopefully, Birnam has, and is ready for a new life ahead at the end of “The Lost Weekend.”