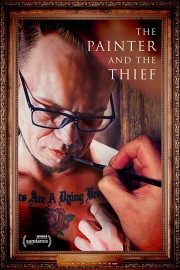

The Painter and the Thief

Society teaches us that criminals cannot be redeemed, that jail is a place for punishment, not rehabilitation. At its best, art shows us that this is simply not true. While some are too far gone for rehabilitation, the empathy capable of being displayed in art can at least give us understanding of why someone is the way they are, what led them down the path they go down. Documentaries are a different beast from narrative, because they show us real lives, and can show us genuine transformation in an individual.

Barbora Kysilkova is an artist, and someone who feels genuine empathy. She just wants to understand. She is an extraordinary artist, from what we see of her paintings. In the first few minutes of “The Painter and the Thief,” we see, via surveillance footage, two of her works stolen from an art gallery in Oslo. In the few minutes after that, we meet one of the men who stole those paintings. Barbora saw him in court, and he has just gotten out of prison. They meet. A couple of times, Barbora presses Karl-Bertil, the thief of the title, for what happened to her works, which were two of her favorites. He cannot remember. But, their bond grows stronger, and he even becomes a muse for her in new paintings. When a car accident happens, the friendship they have goes to another level, as we see in Benjamin Ree’s compelling documentary.

One of the smartest ways Ree’s approaches this unusual and moving story is by following both Barbora and Karl-Bertil, so that we can see both sides of the story, and the friendship that grows out of it. After a while, we forget about the inciting criminal act, and just watch as these two get closer together as individuals. Probably the most emotional moment in any movie this year occurs around halfway into this film, when Karl-Bertil first sees one of the paintings Barbora has made of him. The rapturous pull of art, and a personal connection to it, is brought forth in his face, and the feelings he is experiencing become our own. It’s an extraordinary moment.

Barbora feels like the protagonist through much of the movie, but it’s Karl-Bertil we find ourselves more engaged in. He has a moment in the second half of the film where he is home, and he is telling us about his life beyond the criminal behavior we’ve come to know him from. It starts by seeming like a surprise where we’re supposed to realize that, “hey, there’s more to this person than what he did to Barbora in stealing her paintings,” but the film’s impact already has us there, by virtue of seeing he and Barbora interact. These revelations just add further meat on the bones of that process. We almost feel more of a kinship to him by the end of the film than we do Barbora, an example of the cinematic empathy machine in full-force.

An accident near the midway point of the film puts these people’s lives on different paths, even when the hospitalization of Karl-Bertil brings them closer together. They find themselves separated, as once again, Karl-Bertil finds himself in prison (he’s the one who caused the accident). While there, they lose touch with one another, and it’s almost as if their lives start to spiral downward, as well. Once he gets out, they reconnect after some time, and we learn something interesting about their respective lives apart. It’s almost like they needed the time apart to heal themselves, resulting in healthier individuals, and a stronger connection together. This is one of those stories you’ll leave, and keep close to you for when you need to remember that circumstances, and people, can change. It’s a good reminder to get, every once in a while.