The Passion of Anna

In the late ’60s, Ingmar Bergman made three films that, in truly astonishing fashion, are able to be set apart from the rest of his filmmography in their unique, cinematic nature. The first is, by many people’s estimation, the best: 1966’s “Persona,” and even though it’s been over a decade since I’ve seen it, I’m not inclined to argue. The second one is “Hour of the Wolf,” in 1968, and the third one is “The Passion of Anna,” in 1969. In story, they seem to have little in common, but in cinematic technique, they stand apart from the “Wild Strawberries” and “Seventh Seals” and “Scenes From a Marriages” before, and after, them.

In each film, Bergman includes images and scenes that call attention to the film as a film, rather than a recorded document with an invisible narrator, as most films are. This is never more clear than in “The Passion of Anna,” which not only includes narration throughout, but also includes what appear to be excerpts of behind-the-scenes interviews with the actors discussing their characters. How does Bergman, one of the great masters of cinema, get away with this?

Here’s how I see it. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that these films came when they did in Bergman’s career. With the twin masterpieces, “Wild Strawberries” and “The Seventh Seal,” in 1957, he was already firmly embedded with the greats of the medium. Now, it was time for him to experiment, and I think we can find inspiration for these explorations of film form in the debut film of another master, Andrei Tarkovsky, whose film, “Ivan’s Childhood,” kicked off his career in 1962. It was Bergman himself who said, after seeing “Childhood,” the following: “My discovery of Tarkovsky’s first film was a miracle. Suddenly, I found myself standing at the door of a room, the keys to which, until then, had never been given to me. It was a room I had always wanted to enter, and where he was moving freely, and fully, at ease…Tarkovsky is, for me, the greatest, the one who invented a new language, true to the nature of film, as it captures life as a reflection, life as a dream.”

That last sentiment is the key, I think, to Bergman’s approach in these three films, and “The Passion of Anna” in particular. This is Bergman moving around in that room which he felt Tarkovsky had opened up. What Bergman is doing here is finding new ways of expressing both reality and dream-logic in films, and doing so by showing us, simply, that these are films, and that films are dreams the audience is allowed to experience en mass. By showing us the actors of “Anna” discussing their characters, and how they see the people they’re portraying, Bergman is, in a way, acting as a psychiatrist would, in helping explain the meaning of dreams, and what the people in those dreams represent.

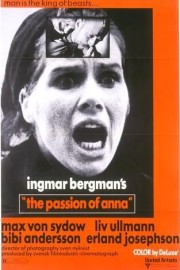

The result is a film that is more fascinating, and more affecting, because we feel as though it is a personal experience for all involved. The story itself focuses on Andreas (Max Von Sydow), a man whose marriage has failed, and now lives in relative solitude on an island in Sweden. One day, a woman named Anna (Liv Ullmann) is frantic, and in need of a telephone. She is crippled, having survived a car accident took the life of her husband and their son. Anna lives with a couple (Eva, played by Bibi Andersson, and Elis, played by Erland Josephson) nearby, and still has nightmares about the tragedy. The four become close friends, and Andreas and Anna become romantically involved. But words about Anna, and the less-than-ideal marriage she had to her husband, that Andreas reads in a letter haunts him, especially with regards to Anna and her husband (whose name was also Andreas), and the potential for physical and mental violence affecting both of them. A man with a less-than-idyllic past himself, Andreas is worries about whatever type of future they could have together, and gradually, the stories they each tell the other about their pasts come undone, resulting in the type of outcome that Andreas feared.

Admittedly, this film doesn’t quite hold my attention the way other great Bergman films have, but it’s an unforgettable film, nonetheless, if only for the ways Bergman played with cinematic storytelling, as I discussed above. “Anna” also points forward to a Bergman masterpiece to come, 1973’s “Scenes From a Marriage,” where Ullmann and Josephson play a couple whose marriage ends, and Bergman shows us how, in vignettes and scenes that came to mind watching some of the most vivid scenes of this film. The lack of perfection is not a hindrance to “Anna,” however; like all experiments, the one setting the test learns from what works, and uses that knowledge towards later tests. As always, Bergman was one of the best when it came to challenging film on its own terms, and always coming out wiser for the next film.