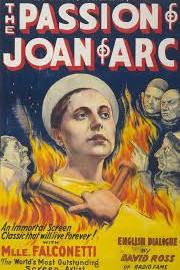

The Passion of Joan of Arc

I’ll admit to watching the 82-minute version of Carl Theodor Dreyer’s “The Passion of Joan of Arc,” rather than the 114-minute version that was more to Dreyer’s vision. I will go back and watch that one, at some point, but even in its truncated for, the film is a remarkable piece of cinema, and one of the most deeply spiritual pieces of film on the nature of faith we’ve ever gotten in film history.

I truly thought I had seen this film in my early years of watching silent films. I’m not sure what I would have thought of it then, but watching it now, one can not only marvel at the way Dreyer composed the film cinematically, but how deeply felt the performance by Maria Falconetti is as Joan of Arc. There’s a profound level of emotion in her work that is singular; more than many performances, it’s one that is built as much out of the way her director tells the story as it is out of her work as a performer. They are very much of a piece.

Dreyer and his co-writer, Joseph Delteil, have simply used details and transcripts from the actual trial of Joan of Arc as their narrative. This isn’t a biopic like others have done, trying to show her life prior to the trial and her death by burning; the film is all about her trial. In focusing on this, Dreyer is not only making a cinematic narrative, but also something of a document of history; essentially, this is a docudrama, and it is, simply, the greatest one we’ve ever seen.

Close-ups are the bread and butter of Dreyer’s style in this film. Rather than show off expansive sets or extravagant costumes, he turns the trial of Joan of Arc into something of an impressionist painting, albeit one that happens to move at 24-frames-a-second. Using intertitles (which have been subtitled) to show us the dialogue is natural, and it helps tell the story, but what is most truly effective is his camera. The way he frames Falconetti’s face, which is as expressive as any in movie history, is a justification of the medium in and of itself. There are frames which are paused as the soundtrack continues, there are crowd shots and scenes where torture devices are seen as something out of a dark nightmare. In a way, the film can seem like a regression from the cinematic form that had appeared codified in Griffith’s films, but in fact, it’s an evolution of it, borrowing from the the great masters to do something that makes him a master himself. It’s as visionary a film as anyone made in the silent era.

What sticks with us, however, is Falconetti. Her unwavering faith as Joan, even when she gives a false confession. The emotion she shows as she’s broken down by the inquisitors. Her fear as they threaten her with pain to get her to confession. Watching her portray Joan’s passion, I couldn’t help but think of “The Passion of the Christ.” Mel Gibson and Jim Caviezel may have brought excessive violence to Christ’s crucifixion, but it’s numbing. Here, there’s almost no blood, but we feel the conviction of her actions, the love she has for God, and for France, much more. Less is more for her and Dreyer, and the result is a lasting work of art.