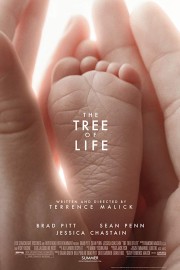

The Tree of Life

As it is with visionaries of cinema’s past– Kubrick, Tarkovsky, Bergman, Aronofsky –the films of Terrence Malick are an acquired taste. I know this because, even having seen all five of his films, I’m still working on acquiring it. I loved his first film, 1973’s “Badlands,” when I watched it during the early days of my film geekdom, but I’m not sure how much I trust those feelings now; another viewing is in order. Meanwhile, his 1978 film, “Days of Heaven,” left me more bored than moved, although since that one carries a film score written by one of my favorite composers, Ennio Morricone, I’m curious to give that one another chance. After that, 20 years past before his next film, an adaptation of James Jones’s novel, “The Thin Red Line,” came to theatres; that film is a thing of visual and musical beauty, but the voiceover meant to engage us emotionally merely feels numbing. As it stands, his 2005 film, “The New World,” which took a new look at the story of Pocahontas and John Smith, has been my “favorite” of his films, or at the very least, the one that I had the most vivid and lasting initial impression of.

Hours after leaving the theatre after Malick’s fifth film, the Cannes winner “The Tree of Life,” I’m still not completely clear where I would place it within Malick’s canon. As with his earlier films, “The Tree of Life” is most resonate as a work of visual and musical art, courtesy the almost experimental cinematography of Emmanuel Lubezki and the blending of classical pieces with Alexandre Desplat’s haunting score. But while I became deeply engaged intellectually by the very personal story Malick tells with such ambition, I still found myself emotionally unmoved, hence my uncertainty of where my feelings lie with it.

First of all, allow me to offer my thoughts on the story Malick is telling here. While “The Tree of Life” encompasses everything from the beginning of time to what appears to be Malick’s vision of the Rapture, the story at the film’s center is that of a boy, Jack (played as a man by Sean Penn, but as a child by Hunter McCracken in a performance that will stay with you), who comes to reject his emotionally abusive father (Brad Pitt, in one of his finest performances) on his quest to become his own man. In doing so, he also comes to question the existence of God, or at least question the greatness of a God that would allow bad things to happen to good people, like the death of a young boy around his age in a local pool. Death will also strike Jack hard in adulthood, when one of his brother’s passes away, leaving his family broken once again later in life. Whether the scenes of Jack as a boy are flashbacks by Jack the man at the time of his brother’s death, I am still not completely certain about, but I’m not really sure that matters, as anyone who follows Malick’s ambitious way of telling this story will likely not be asking themselves such questions until after they leave the theatre anyway.

As with “The Thin Red Line” and Malick’s other films, the writer/director uses voiceover less to convey the story and more to set the tone of the film. As with those prior films, I could have done without; there are many words said, but it all feels like empty prose– the film would have been much better as a silent movie. Dialogue is not necessary to tell the stories Malick is interested in, and title cards would have been just as effective in having his characters say what they want to say. This has been a constant complaint with me when it comes to Malick’s films, which says as much about the importance of music and images in his films than it does his skills as a filmmaker, although it does make the praise of those who call him a genius feel less deserving. Malick isn’t a genius on the level of Kubrick, but he is every bit as iconoclastic and ambitious in the films he makes, which alone gives his films worth, regardless how problematic his approach to filmmaking is.

So, it is actually a few days after seeing “Tree of Life,” and my feelings about the film are no longer so uncertain; leaving “Badlands” out of the equation for now, “The Tree of Life” does rate as probably the “best” of Malick’s films, although his best still lags behind even the weakest links of Tarkovsky’s, Aronofsky’s, or Kubrick’s filmographies. Even this film, arguably the most stimulating he has made on an intellectual level, was unable to move me emotionally. His actors, including Jessica Chastain, whose ethereal presence as Pitt’s wife has garnered her much acclaim, are not playing fully-realized characters so much as ideas of characters, making it difficult for the audience to engage with them on a personal level. Some have, but I couldn’t, although personally, the stimulation I felt in simply watching and processing Malick’s film, which even takes us back to prehistoric times in some of the film’s most striking scenes, has been more rewarding than in years past. And word came as the film hit Cannes that Malick has another film on the way next year. Considering that “The Tree of Life” is only his fifth film in 38 years, I can’t wait to see what images inspired Malick to get back to work so quickly.