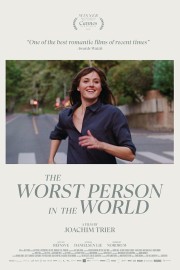

The Worst Person in the World

One of the worst things we, as a society, can do is put sanctions and hardwired rules on where people are supposed to be at a certain age. Certainly, there are biological issues which makes something like, say, pregnancy, riskier when you’re older, but when it comes to things like jobs, love, and housing, not knowing all of the answers right out of the gate when you hit “adulthood” is not a bad thing. In fact, it makes you completely normal, and if there’s something we should maybe do more of in K-12, it’s emphasize that, if you don’t have it figured out by 25, that’s alright. Same at 30, 35, 40, and on and on. The most important thing is that you’re moving forward; if we feel stuck in an area, that’s where life begins to get really hard.

As I was knocking on the door of 30, I had a lot of pressure from society, and especially my parents, to figure it out. I wasn’t even close to getting married, was just over five years of being at the movie theatre, and still living at home. But when my parents were nearing 30, they were having me. That’s the moment where I kind of said, “fuck it,” and realized that my life wasn’t going to be like my parents’s, and if I tried to force it to be, I was going to be more miserable than I already was. It would take me another decade, and almost that long in therapy, to really be close to getting married and moving out, but by that point, I was more certain of myself, and knew that’s what I wanted, and how I could be happy.

In “The Worst Person in the World,” co-writer/director Joachim Trier shows us four years in the life of a woman going through this emotional struggle, and trying to figure it out the best she can. One of the things that is so beautiful about the script Trier and Eskil Vogt have written is that Julie (Renate Reinsve) is simply trying to work things out for herself. This isn’t a movie looking at tropes in narrative but showing the ways in which life can simply be random and unexpected in the choices we make. Using voiceover at times to go with a chapter structure, the film is not about a long arc but moments that matter. The arc is life; the story is going from unhappy and uncertain moments to a moment where certainty and happiness exist, which will not happen until the epilogue. It’s a phenomenal, emotional experience.

Julie starts out as a med student, until she decides that’s not for her anymore, so she moves to a psychological track. She finds that she is more interested in the intellectual than the physical. But even then, she finds herself not entirely satisfied; she’s more interested in the visual, so she takes her student loan, and puts it to photography. Along the way, she meets a comic book artist (Askel, played by Anders Danielsen Lie) who’s a bit older than she is, and is thinking about other things. One day, she meets a barista (Elvind, played by Herbert Nordrum) when she crashes a party. They flirt, but don’t really cheat on their respective partners. Askel is at the point where he wants kids, and he thinks Julie will be a good mother, but a chance encounter with Elvind in the bookstore she works at makes her think of the possibilities. Choices are then made, and there’s no looking back for Julie. Is there?

Agency is a word that has gained a lot of notice when it comes to personal choices, and fundamentally, “The Worst Person in the World” is about a woman with agency. Julie is the clear main character in this movie; Askel and Elvind are in the next ring of importance, while everyone else is in the background- if they have a bearing on Julie’s agency in life, they’ll move more to the center, but fundamentally, nothing they do matters. The way Trier shows us the good, and bad, in Julie, while not letting her off the hook in some of her choices, is one of the strongest aspects of this film. If we want to judge her, we can, but since so much of the film we are resolutely with her point-of-view, it’s hard to judge even moments, like when she realizes she cannot be with Askel anymore. That moment leads to the film’s centerpiece sequence, where time stops, and she goes to see Elvind. It’s a beautiful scene that gives us an external expression of internal feelings, and it is a triumph of what makes movies special.

The film balances warm humor and, what could be, maudlin drama, wonderfully, largely because of the humanity Reinsve invests in Julie. When it gets to the final act of the film, we cannot help but tear up because of the way the story has unfolded, and how it gives Julie and Askel a moment of peace and closure that is so important when it comes to relationships that mean something to us, regardless of whether they continue or not. A movie like this invests its heart into trusting us to invest ours in it. I was rewarded, I feel, with one of the most emotional experiences a film has given me in a while.