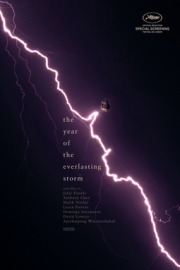

The Year of the Everlasting Storm

In the beginning, director Jafar Panahi is in his home in Iran. He is watching birds and his pet iguana when he gets someone buzzing to be let in. They are in what looks like a hazmat suit. He and his wife buzz them up, wondering if one of their neighbors is sick. It is his mother, coming to visit- she has taken all the precautions in the age of corona. We see emotional video calls with grandchildren, and a dynamic between the mother and the iguana that will take a surprising turn by the time life is being born.

In Wuhan, China, director Anthony Chen tells us of a family of three struggling in the early days of the pandemic. Working from home, and lost wages, cause tension while raising a young child, with a father who has a hard time being a caretaker. Isolation does not sit well with them. Malik Vitthal has a father trying to see his kids during the pandemic. They were taken away from him after he and their mother proved to be irresponsible; he is trying to set things right, though.

Filmmaker Laura Poitras collaborates with Forensic Architecture to look into abuses and the infiltration of Pegasus spyware around the world. Meanwhile, in Chile, Dominga Sotomayor looks at a mother and daughter whom break quarantine to see the other daughter’s new baby. In Texas, director David Lowery takes us on a journey with a woman who reads letters she discovered from a father to a son about the death of his other son. Finally, director Apichatpong Weerasethakul puts a light to a bed in Thailand to look at the insects it attracts.

Omnibus, or anthology, films always feel like a mixed bag. Even when there are uniformly great filmmakers involved, it’s inevitable that some of the short films included will be better than others. In “The Year of the Everlasting Storm,” we get seven films from seven directors whom are looking at the COVID-19 pandemic through unique lenses, whether it takes a macro look at the subject like Poitras’s “Terror Contagion,” which looks at how government surveillance is being exploited to silence dissidents and others against said government, and how the company behind Pegasus has found its way into the contract tracing business during COVID, or something as simple as a family struggling such as in Chen’s “The Break Away.”

It’s been interesting to see how filmmakers have approached the challenges of COVID in making their movies, and COVID as a subject. At Sundance this year there was a film from Brazil called “The Pink Cloud,” which was made pre-pandemic, but reflects the anxiety and difficulty the past two years have had on a lot of people. “The Break Away” feels cut from the same cloth, but knowing that it was made during the pandemic makes it feel more authentic, and emotionally-charged. Lowery has made a film that reflects our relationship with film itself in “Dig Up My Darling”- after all, what is the act of moviewatching but getting glimpses of other lives to get lost in? Weerasethakul has what might be the most interesting take on COVID, by using that most intimate of places as a petri dish for the natural world, he’s showing us one of the most likely ways the pandemic started in a simple, and unsettling, manner.

Naturally, we will always find ourselves ranking films in something like this, so that’s as good a way to end here. Panahi’s “Life” was my personal favorite because of the surprise it takes at the end, with “Dig Up My Darling” and “The Break Away” next. Weerasethakul’s “Night Colonies” made for a compelling finale, while Vitthal’s “Little Measures” and Sotomayor’s “Sín Titulo, 2020” are nice, personal stories of family. While “Terror Contagion” is compelling from a substance perspective, it also stops the anthology in its tracks from a narrative standpoint. I don’t think it would have worked at the end, but I don’t know if it was necessary for inclusion in this film. For all its highs and lows, however, “The Year of the Everlasting Storm” is a creative, thematically interesting exploration of the year the world stopped, yet was forced to keep going for many of us.