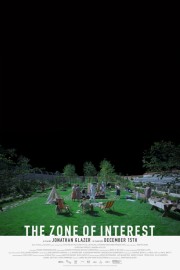

The Zone of Interest

I think the most important dialogue in Jonathan Glazer’s “The Zone of Interest” is a scene between Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel) and his wife, Hedwig (Sandra Hüller), at the edge of a stream that is near their home. Rudolf has just told her that he is being transferred, and she is wondering what will come of the home they have made for themselves and their children. Hedwig hopes they can stay behind at this home, as it is representative of the life they have been promised; they are fulfilling the dream of Germany its leader espouses. That leader is Adolf Hitler.

The reason this dialogue stands out for me is because in having it, Hedwig and Rudolf have no sense of awareness that they couldn’t just live out their lives in peace after the war. Their home is right next to Auschwitz; we see its watchtowers and walls, but do not see inside until the very end. The Höss’s are oblivious to the idea that they could suffer any consequences for the deeds inside the camp, even though Höss is the commandant of the camp when the film begins, and is being summoned back to it at the film’s ending. In the background of the action at their home, we hear trains, rifle fire, dogs, screams, and the incinerators going. We are acutely aware of the atrocities occurring on the other side of the wall, even if the characters aren’t. This is a film about exposing not the horrifying atrocities of the Nazis, but the complacency of those who refused to do anything to stop it, and it is haunting.

Glazer is adapting a 2014 novel by Martin Amis, which has- based on my awareness- a more straightforward dramatic narrative than the film Glazer has made. As it went along, I couldn’t help but think this would be a film about the Holocaust that Stanley Kubrick would make; we know he was planning on making one before “Schindler’s List” was released. Glazer’s approach to the subject is at a distance, but makes us aware of its horrors at every moment through its use of sound, and its use of casual apathy towards those sounds. The novel’s main characters were inspired by the Höss’s, but Glazer removed all pretense, researched the actual people, and it’s an important choice to have made. It’s the reason the scene I highlighted earlier stands out more, as we can learn that, in real life, Höss was punished for his part in the Holocaust. The disregard for human life outside of one’s circle is Glazer’s ultimate theme, I think, and it’s something we see in many ideological extremists not just historically, but today.

An enormous part of “The Zone of Interest’s” impact is its soundscape. As I mentioned, we only hear the sounds of the concentration camp on the other side of the war. In this choice, Glazer is adding a layer to the story being told to us visually, and letting us experiences how apathy towards suffering in a profound, unique way. In a sense, it is the same idea as the “girl in the red coat” sequence in “Schindler’s List,” but a different approach. As the movie ends, and we let it sink in, the sounds are what linger longest, in a way. Glazer’s lack of a score also leaves a mark; collaborating once again with Mica Levi, Glazer opted to not rely on a musical score; the only music in the film is either from an on-screen source, or when Levi’s experimental sounds are laid in over images of a local girl, at night, stealing apples and put them where the prisoners in the camp will work the next day. These scenes are shot in an inverted color scheme, making them feel more like the act of someone rebelling against societal norms at this particularly point in history, which of course, they were, as these actions would have certainly gotten her killed. She is whom we hope we might be when faced with such inhumanity; sadly, however, we might more often be those going about our lives, actively not listening to the pain of those around us. In making this film, Glazer is challenging us to shift the other way.