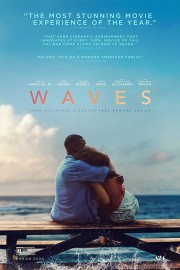

Waves

The biggest complaint that one can levy against Trey Edward Shults’s “Waves” is that, at 135 minutes, it is more than a little long in the tooth. When it comes to the story it is telling, though, I was fully enraptured as Shults takes key stressers for the character whom, at the time, appears to be the main character, and throws them into the story like rocks thrown in to a pond, and watch what ripples occur. Seeing how the characters react, seeing what transpires, is what Shults is interested in here, and his way of approaching it is immersive and emotional to watch.

The film begins with focus on Tyler (Kelvin Harrison Jr.), the son of a suburban family whom has a promising wrestling career going in high school, and a loving relationship with his girlfriend, Alexis (Alexa Demie). His father, Ronald (Sterling K. Brown), has been pushing him to be his best, and helping with his wife, Catherine (Renee Elise Goldsberry), with her family’s business to help give Tyler and Emily (Taylor Russell) the best life they can have. Tyler’s shoulder has been bothering him, though, and when Alexis gives him some news, things begin spiraling for him, and the family may be left in his wake.

There’s some sly storytelling going on here by Shults, to where, when something huge happens through the actions of one character, the narrative is continued by another one. He’s reached a logical conclusion to the one story, and its painful; what he does now is decides to see how that impacts another character, and it’s the type of narrative trick that makes “Waves” a fitting title. Shults wants us to experience what these characters are feeling from the inside, and it’s a slight of hand that is effective in the moment, and inspiring when we think about it afterwards. It’s funny how, in the plot descriptions I’ve seen about “Waves,” it points out the father, played wonderfully by Brown, but the film is about the kids. But Ronald, Brown’s character, has an important part to play, and it’s interesting to see how he reacts to what we’re watching, and Brown has a scene near the end that is such a powerful moment it would merit awards consideration on its own. In a way, he is the catalyst for Tyler’s behavior, but when push comes to shove, Tyler is responsible for how he behaves. Harrison is fantastic in a heartbreaking character, someone who seems to have everything going his way, but gradually finds himself losing it all, in part because he internalizes his anxiety, and doesn’t communicate about what’s going on with him. Once it gets to a certain point, however, nobody can stop him, and the results are inevitable, as are the breaks the rest of his family, especially Emily (played by Russell in one of the year’s great performances) will experience afterwards.

As much as the film is about characters and narrative, Shults has cinematic ways in which he tells the film, using cinematography to help us get into mindsets the characters are in, and music to help enforce the emotions. The camerawork by Drew Daniels, with an assist by colorist Damien van der Cruyssen, shifts aspect ratios and sometimes moves with dizzying abandon as we are put inside the lives of this family, how they spin out of control, and how they snap back into focus. Musically, there’s a lot to process with the films use of songs, coupled with a score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross that continues their run of unusual soundscapes with unexpected emotional resonance to the events being shown. Both work at the service of Shults’s storytelling, and if it seems that they overpower it, it’s only because Shults intends it that way while he shares this story of pain and passion with a family trying to find their way.