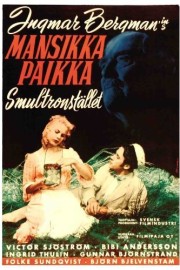

Wild Strawberries

Ingmar Bergman’s “Wild Strawberries” is the film that, along with his OTHER 1957 classic, “The Seventh Seal,” propelled him to the realm of the great filmmakers. In the 50 years after, until his death in 2007, he never left their ranks, and improved his standing with films such as “Hour of the Wolf,” “Persona,” “Scenes From a Marriage,” “The Magic Flute,” and his final film, “Saraband,” among many others I have yet to see.

Of all of his movies, “Wild Strawberries” is probably the one that resonates the strongest with me from an emotional standpoint. It’s a rather simple story– an aging professor, while travelling to receive an honorary degree, revisits his youth through daydreams and going to his childhood home –with a profound message of redemption and acceptance of our faults. No other filmmaker in the history of cinema has been so strikingly personal, and “Wild Strawberries,” though not his first film, is, arguably, the first that led Bergman on his path towards self-reflection, from which he would never deviate.

After a brief prologue, and the opening credits, Bergman begins with an ambitious, extended dream sequence in which the professor (Victor Sjostrom) is walking down an empty street. He goes to check his watch for the time, only to find it is without hands. He sees a man on the sidewalk, but when he goes to speak, the man’s face is painfully made-up, and he falls to the ground, and liquefies. Then, a horse-drawn carriage carrying a coffin races past, only to get stuck on a lamp post. A wheel comes off, and the carriage only gets going again once the coffin falls out. It opens, and the professor goes to investigate, only to see that the body it carries is his own. Then he wakes.

The film is told in a series of vignettes, as the professor and his daughter-in-law (Ingrid Thulin) drive to the ceremony for the old man’s degree. They make several stops along the way: at the professor’s childhood house; at a gas station, where the attendant (Max von Sydow) reminds him of the good he’s done; at his mother’s house before finally arriving at the University for his ceremony. Along the way, the old man has dreams of his youth, in particular, revolving around the failed courtship of a young love (Sara, played by Bibi Andersson) who eventually went on to marry, and have a family, with his cousin.

This is the sort of film that is almost impossible for American filmmakers to pull off; more often than not, they resort to melodrama and rank sentimentality to tell their story. And yet, foreign filmmakers, with their unique, cultural sensibilities, are able to achieve greatness with such materials effortlessly. Most of the time, Bergman told such stories through a pain and spiritual emptiness, but in “Wild Strawberries,” it feels as though the great director was optimistic about what could await the professor as he reconciles his memories with his feelings at the end of his life. Part of that comes, no doubt, from the trio of young people the professor and his daughter-in-law pick up along the way. They are headed to Italy, but have time to join the pair on their journey. The girl of the three, Sara (also played by Andersson), finds herself taken by the professor, and him by her, as she reminds him of his lost love, and that connection seems to help the professor in his emotional journey. At the end of the film, the professor seems at peace with himself, and his life. Unfortunately, that peace would not be attainable by many of Bergman’s later protagonists, which is part of why I probably value it so much in this film. Of course, the older he got, the more life showed Bergman the type of suffering and loss that would later inform his films, and make the optimism I sensed in this film move further and further out of reach.