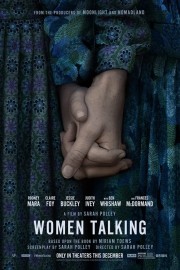

Women Talking

Films where most of the drama takes place in a single room are tricky to get right. If the writing and directing aren’t top-notch, the resulting film might be preachy melodrama. In her adaptation of Miriam Toews’s novel, Sarah Polley cuts through any pretenses of the melodramatic and right to the heart of her subject, which is the need for women to be heard, and for men to listen. “Women Talking” is another example of Polley taking on a subject that is challenging to our emotional comfort zone, and allowing us to feel our way through it as the characters do to look at things from a different point of view. That can be the very essence of great cinema, something Polley has been particularly adept at creating in most of her other films as a director (“Away From Her,” “Stories We Tell”).

As more and more women (and men) have felt empowered to speak out about the sexual abuse that they’ve faced over the years, it’s important that other people- especially those whom have not experienced any such abuse or harassment themselves- to take a backseat, and just listen to those who have. In an era where social media rewards those with the hottest takes or the loudest opinions, that can be difficult to do. By setting this story in an isolated religious colony, and then isolating much of the story further in a barn, where everyone has a captive audience, Toews and Polley don’t give the audience a choice but to listen, and to hear where everyone is coming from, regardless of whether we think they’re right or not. Our opinions don’t matter; only how open we are to what they have to say.

Three generations of women from this colony are gathered in the top part of a barn to discuss what they are going to do about the sexual assault that has been pervasive among the men in their colony. Through their words, we gather we are being let in on an open secret the colony has lived with for as long as they can remember. One of the latest victims, Ona (Rooney Mara), is pregnant with a child from the most recent assault. The women are there to decide what they will do moving forward- stay in the colony, and “forgive” their attackers, which is certainly what the elders of the community want; or leave, en masse, and enter a world with its own challenges. The minutes of the meeting are taken by August (Ben Whishaw), the son of a family who left, and whom has returned and been welcomed back. Throughout the long hours of the meeting, we hear a variety of vantage points on the matter, from elder women whom have endured abuse themselves, to the younger generation, both married and not married, and from children, one of whom was recently attacked. Her attacker is in jail, and has supposedly given names, but they don’t know if that will last. They have to weigh the pros and cons of each scenario, and decide what is best for them as a group.

Polley does not show us the abuse, but the aftermath of it for some of the women and children we hear from. She is not out to exploit our feelings on the subject, but to share the feelings of the characters. Her camera is more interested in watching these women work through their traumas, and the thoughts they have as a result of them, then to see them exact any sort of revenge. This is about working through grief together. If there’s a comparison to be made, I actually want to say it’s with “12 Angry Men,” where gradually, viewpoints are heard out before they come to a collective opinion they can all live with. The important thing is to hear everyone out, and understand where each woman is coming from. Some want to just up and leave. But what about the boys left behind? Well they can come to, if they want. Should there be an age limit to which ages get to come? Well how about we give the men a chance to come with us also? Some of these questions seem ridiculous, but in listening to the women explore them in the film, we get why they should be asked. After all, this is a massive change to not just their living situation, but their way of life. Some are more willing to take the leap of faith than others; some would rather stand their ground, but in doing so, they might lose something of themselves in the process. It’s easy to just say, as an outsider, “why don’t they just leave?” “Women Talking” helps you understand why that’s not as simple a question as it seems.

The main actors we hear from are Mara, as a woman whose conflicted feelings are rooted in her preparing to raise a child herself; Claire Foy as Salome, a mother who feels like fighting for her children means standing up for herself against her abuser; and Jessie Buckley as Mariche, a mother who is comfortable forgiving if it means comfort for her family. All three shine at bringing out the emotions each character is feeling throughout the journey they take in this film. Whishaw is another standout, as a man tasked with just listening to these women- in a way, he could be seen as a stand-in for the men of the colony, but as we learn, there’s a reason his family left, and why he is the ideal choice. Frances McDormand is a woman who is so dug into the tradition of the colony that she only sees the way forward as the way it’s always been. Judith Ivey and Sheila McCarthy are a pair of mothers whom see leaving as the best option, but show understanding through their wisdom and empathy. The performance I think a lot of people will have a hard time shaking, though, is August Winter as Melvin, whose abuse has silenced him, and changed him profoundly. When an actor is left to be mute by a role, it’s always fascinating to see what they project, and when Winter has his big moment, it’s the moment that shattered me most because it gets to the heart of what these women are doing- making sure that, in spite of what’s been done to them, their voices are heard.

“Women Talking” has narration throughout, as a mother talks to their daughter, telling them that their life will not be her mother’s. That’s what we should hope for most when women talk- that, when people listen, the results is a life better for those that come after. The women in this film don’t know what’s to come for them as the credits begin to roll, but it’s certainly comes with hope for a better tomorrow. Ultimately, I feel like that’s what Polley does in her films- ask us to think of what’s best for people in the future, even if the moment is difficult. I’ll always be open to listening to her whenever she says something.