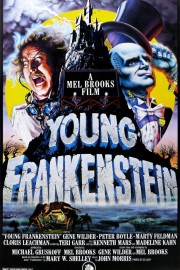

Young Frankenstein

I wrote about Teri Garr’s performance in “Young Frankenstein” over at In Their Own League here.

A funny thing happened to me as I began watching Mel Brooks’s greatest parody, “Young Frankenstein,” for this week’s “A Movie a Week” column. Rather than thinking back at the history of modern parody films, which Brooks defined with both this and his other great 1974 film, “Blazing Saddles,” my thoughts drifted towards Tim Burton’s 1994 film, “Ed Wood.” A curious comparison, I know, because Burton’s film wasn’t a parody, but a biopic, even if it was about one of the most eccentric filmmakers of all-time. That being said, as I began watching “Young Frankenstein” again, I found some connective tissue between the two films.

First and foremost, there are the stylistic similarities. Both films are shot in black-and-white, which is the only real way for them to truly pay homage to their subjects, whether they be the classic monster movies of James Whale in this film, or the surreal, low-budget camp of Wood’s films in Burton’s movie. The sets and costumes are period-perfect evocations of their subjects, and the musical scores by John Morris (for “Frankenstein”) and Howard Shore (for “Ed Wood”) complete the homage with scores both knowingly comic but richly emotional.

I think the biggest reason I thought of these two movies together, however, was in the obvious affection they have in tackling their subjects. For Burton, his love of Wood and his work is evident in every frame, as we come to see the infamous director of “Plan 9 From Outer Space” and the “Beetlejuice” filmmaker as kindred spirits. For Brooks and his co-writer/star, Gene Wilder, they love the films James Whale made based upon Mary Shelley’s writings, and even the progressively formulaic sequels that were made, which gave Brooks and Wilder the freedom to make their main character a descendant of the original Frankenstein, who finds himself drawn into the mystery and madness of his grandfather’s work. What makes “Young Frankenstein” so wickedly, and brilliantly, funny, however, is that Brooks and Wilder take the emotional journey of Frederick von Frankenstein so seriously.

I don’t need to do a run down of the story, do I? Hell, I could spend the entire review quoting the film if I wanted to. “Could be worse.” “How?” “Could be raining.” Cue rain. “What knockers!” “Thank you, doctor.” “Whose…brain was it?” “Abby someone.” “Abby someone.” “Abby…Normal.” “Abby…Normal.” “Put…the candle…back!” “Call it…a hunch.” And, of course, “Sedagive?!” But simply quoting the great script by Brooks and Wilder isn’t enough, especially considering how spot-on the film is in poking fun at “Frankenstein” and it’s great sequel, “Bride of Frankenstein.” Brooks nails the Victorian look of Transylvania and the Gothic feel of Frankenstein’s castle and laboratory, which uses actual sets and props from the Whale films. And then, there’s the cast of characters this story needs: Marty Feldman’s sarcastic hunchback assistant, Igor; Teri Garr’s curvy, potential love interest, Inga; the marvelous Madeline Kahn as Frederick’s socialite fiancee; William Mars as the wooden armed police inspector who will lead the eventual riot on the castle; and, of course, there’s Cloris Leachman’s terrifying housekeeper, Frau Blücher. (Cue frightened horse neighs.)

The two performances that make the film a real classic, however, are Gene Wilder’s as the manic, driven scientist who, having spent a lifetime running from his family’s legacy, ends up embracing it fully, and Peter Boyle as the Monster. There’s not much I can really say about Wilder that hasn’t, probably, been said before; Wilder’s performance is a perfect calibration of pathos and over-the-top comedy, using physical acting and different levels of verbal performance to bring the character the life in a way that rates him with the greatest mad scientists in film history. However, Boyle’s Monster is the unsung hero of this film. Of course, he’s best known now for his gruff work on “Everybody Loves Raymond,” but his largely silent work in this film is the greater triumph, in my opinion. Like Karloff in the original “Frankenstein” films, Boyle projects so much through his imposing stature, and his eyes, which Brooks uses for maximum effect as we see the Monster not just in moments of terror, but in trying to understand human behavior, and emulate it, most famously in the scene with Gene Hackman’s kindly, blind hermit, but also with Kahn’s Elizabeth. All of that is brought to center after Wilder’s Frederick attempts to balance the abnormalities in his Monster’s brain with his own intellect, giving the Monster a voice to express himself. It’s the connection between Wilder’s and Boyle’s characters, both of whom are trying to live up to their responsibilities as scientist and creation, that gives “Young Frankenstein” a disarming sense of humanity and feeling that makes the outrageous comedy that drives the film all the more potent. Yes, Brooks continued to make hilarious homages in the years after “Frankenstein” (I have a soft spot for “High Anxiety,” “Spaceballs,” “Robin Hood: Men in Tights,” and the movie version of his musical hit, “The Producers”), but even I can admit that without the emotional connects he and Wilder forged to this material in particular, Brooks never came close to matching this masterpiece.