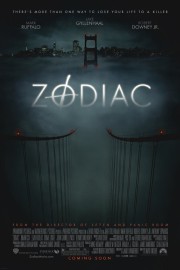

Zodiac

**I also wrote about “Zodiac” as part of Film for Thought’s “Ultimate Choice” blog on favorite David Fincher films here.

For 15 years now, David Fincher has been responsible for films that are dark, provocative, unsettling, and sometimes wickedly clever both in structure and wit. From his deeply flawed feature debut “Alien 3” to his hollow- but intriguing- 1997 thriller “The Game” to three films with rabid followings, and polarizing critical and audience responses (his 1995 serial killer thriller “Se7en,” his 1999 cult sensation “Fight Club,” and his 2002 Jodie Foster thriller “Panic Room”), Fincher has developed into an iconoclastic, visually-exciting filmmaker who can make even the simplest plots grab an audience through a steadily-evolving storytelling finesse and a sharp eye for casting.

Both of those characteristics elevate “Zodiac” into one of his best films, and one that immediately stands out in what’s so far been a very slow movie year. Thankfully, Fincher hasn’t made another “Black Dahlia,” where flash dominated an intriguing- albeit fictionalized- true story of a tantalizing unsolved murder.

Instead, Fincher’s gone back to the brooding, straight-forward visual approach of “Se7en” to bring Robert Graysmith’s detailed bestsellers (providing the blueprints for the probing screenplay by James Vanderbilt) about the Zodiac murder investigation in the 1970’s that rattled the San Francisco area and baffled investigators for decades after. The case was never officially solved, but Graysmith- a cartoonist for the San Francisco Chronicle who became obsessed with the case (and played here by Jake Gyllenhaal with an everyman charm and dogged determination that makes him an ideal protagonist for the story)- and other key investigators followed the information to their own conclusions, with only no hard evidence and death itself stopping them from closing the book for good on Zodiac.

Fincher’s primary influences outside of his own oeuvre are also based on true stories- Alan J. Pakula’s “All the President’s Men” (the classic Watergate investigation thriller, which Fincher evokes in the deft hi-def cinematography by Harris Savides (and pays homage to by employing that film’s composer, David Shire, who provides “Zodiac’s” moody score)) and Oliver Stone’s “JFK” (which had the same breakneck, go-for-broke pacing in delivering information to the audience visually and verbally). The main story theme that connects the three films is obsession. Woodward and Bernstein’s obsessive drive for the truth in “President’s Men” leads to what is still the most bracing scandal in American political history. But they managed to avoid paranoia, and were able to get their man. Like “JFK’s” Jim Garrison, Graysmith and the other main investigators of the Zodiac- namely, San Francisco Chronicle writer Paul Avery (played by Robert Downey Jr., continuing his career renaissance with another charismatic and idiosyncratic performance) and San Francisco PD detective Dave Toschi (the no-bull turn by Mark Ruffalo is equal parts hot-shot cop- like the one he played in Michael Mann’s “Collateral”- and self-destructive conspiracy theorist as the cracks in his steely persona- he was the inspiration behind Steve McQueen’s character in “Bullitt”- begin to show)- develop hunches that lead them to one prime suspects, and obsessions with the details of the case that estrange them from family (Chloe Sevigny’s stare of disapproval as Graysmith’s neglected wife could melt lead) and friends (Avery’s turns to vices that’ll eventually kill him, while Toschi’s partner- played by Anthony Edwards (just one major supporting character in a cast stacked with top character actors)- eventually drops the case for the sake of his sanity). The cases all make are convincing, but eventually ineffectual due to a lack of tangible evidence, and- in the case of Zodiac suspect Arthur Leigh Allen (played with a haunted glint by John Carroll Lynch)- death in 1991. That the case remains open in many California counties is part of its’ allure, even as the credits start to roll.

That the film leaves an unmistakable mark on its’ audience- whether the viewer followed the Zodiac killings or not- is a testament to Fincher, who puts away many of the stylistic tricks of his trade (though an inspired nod to the ingenious visual overlapping sometimes prevalent in “Fight Club” works as the Zodiac obsession begins) to present the story as what it is- a police procedural with a conclusion that’s factually open but emotionally closed. His film isn’t critic-proof, though; while it’d be impossible narratively to cut any scenes, the film feels the full weight of its’ 2 1/2 hour running time during a middle section where time passes and the case comes to a halt as leads dry up (confession- I slept through much of this section my first two viewings; my third time, however- wide awake). But he follows his characters down the case’s maddening labyrinth, and shows the brutality of Zodiac’s murders with unnerving, uncompromising honesty.

Start with the murder that opens the film- with an air of impending danger lingering, we watch as a married woman and her young fling drive to lovers’ lane, but are unable to relax when a strange car has followed them, and blocks them in before the driver comes out and coldly shoots them. Later, Zodiac murders a couple in broad daylight by a lake. In few other movies has violence been so visceral and paralyzing, forcing you to watch helplessly, in shock of what you’re witnessing. Later still, Zodiac’s murder of a cabbie is shot with the same stark realism. There’s not a lot of violence in the film (I’ve basically listed it all here), but what there is lingers long in the memory, and can lead to the same disillusioned probing for both a factual- and emotional- truth that will later take its’ toll on Graysmith, Avery, and Toschi. Still, that determination to search for the truth, regardless of the personal consequences, makes “Zodiac” worthy of comparison to Pakula’s “Men” and Stone’s “JFK.” And like Pakula and Stone before him, it’s Fincher’s conviction, and unflinching look at the reality of his tragedy, that makes him a filmmaker worth following down the dark side of humanity. Sign me up for his next visit there.