One of the first pieces of long-form film criticism I wrote was in an English class in 1997. We were to choose a subject, and build an argument about our thesis statement. This was the same class in which I also wrote about the movie ratings system, but I don’t know if I have the original assignment still. This week, I decided to recreate it with new eyes on the films. I hope you enjoy!

In 1996, two of the best films of the year explored multiple facets of kidnappings, but while Joel and Ethan Coen’s “Fargo” and Ron Howard’s “Ransom” could not be more different cosmetically, thematically, they look at the desperation, and moral ambiguity, that can occur in such a scenario in ways that link them more than you might expect just looking at them. At the time, I looked at these two as the very best films of the year; while that holds true for “Fargo,” “Ransom” is much more of a popcorn flick now, with other, better films pushing it down the list for me. There’s still plenty to explore in these two, seeing them as two sides of the same coin, however.

Let’s begin by looking at the male leads in these films. In “Fargo,” Jerry Lundegard (the excellent William H. Macy, in an Oscar-nominated performance) is the one initiating the kidnapping that is about to put this story in motion. A husband and father, he is hiring two criminals to kidnap his wife so that he can get money from his father-in-law, who doesn’t respect him. Jerry is not an intelligent character, and he’s an amoral one; he’s giving the criminals a car from the car dealership he runs so that they can drive to Brainard from Fargo, North Dakota to pull this job off, he doesn’t seem to have any qualms whatsoever with his wife being taken, and the trauma that might cause her, and he’s not only bilking his father-in-law for money, but he’s also lying to the criminals about how much the ransom is, so that he can take most of it for himself, and leave them with a drop in the bucket. If the movie hadn’t been pitched in such a darkly comedic tone by the Coen Brothers, Jerry would be as sociopathic as Anton Chigurh from “No Country for Old Men”; as it is, he’s just a pathetic sad sack, where even the simplest misfortune like struggling to scrape the ice off of his car is funny. As the walls close in on him, we feel no sympathy, and his attempts to cover up what he’s done play as comedy, not tragedy.

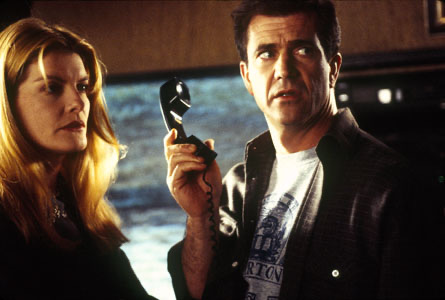

Tom Mullen (played by Mel Gibson in one of his best performances) is not far removed from Jerry, but his actions show a level of sympathy Jerry simply cannot illicit from the audience. “Ransom” begins with Mullen and his wife hosting a party in their swanky New York apartment. A successful businessman, Mullen has built his fortune from the bottom up, and has made a good life for himself. But there have been whispers of impropriety to keep his business afloat, involving a bribe to head off a union strike. When we see Tom with his family, however, we see him as a fundamentally good man, though, to where we feel the immediate anxiety of not being able to find his son when they are in Central Park. From that moment, our sympathy is with Tom, and the anguish when they receive proof of life is genuine on Gibson’s face. Against the kidnapper’s wishes, they call in the FBI that just investigated Tom to help them navigate the situation. By the time they arrive, he already has the money ready to go. It turns out, however, that the allegations against Tom are true- like Jerry, he’s not above doing something shady to protect himself- and even though they are able to rule out the man in prison because of what Tom did, that instinct of Tom’s to do whatever he needs to do for his family will play itself out in unexpected ways that will test his marriage, and the support he gets from others, if it backfires on him.

Both kidnappings backfire, and lead to deaths that could have been avoided. In “Fargo,” Carl and Gaear (Steve Buscemi and Peter Stormare) end up killing three people after they get pulled over when returning to Fargo after kidnapping Jerry’s wife, and when Carl returns to get the money, two more are killed, and he is shot in the face. All of this could have been avoided had Jerry just been upfront with his father-in-law, and not felt the desperation to resort to this ridiculous scheme to make some money. In “Ransom,” the kidnappers- led by a corrupt cop (Jimmy Shaker, played by Gary Sinise)- make Tom go through hoops to make the initial drop, but a lie to Tom about how he can get his son back leads to a botched drop, and the death of one of the kidnappers (played by Donnie Wahlberg), the only one who appears to have any sympathy for Tom’s son. It also leads Tom to think that maybe he won’t get their son Sean back regardless of what they do, leading to the big twist in “Ransom,” when Tom goes on TV, and tells the kidnappers that their ransom has now turned into a bounty. It’s a desperate move on Tom’s part, one that he is alone in thinking is the right one (and leads the main FBI agent on the case, played by Delroy Lindo, to tell Tom’s wife the truth about his checkered past), but it also leads to desperation from the other kidnappers (played by Lily Taylor, Liev Schreiber and Evan Handler), who want out of this situation. Jimmy is resolute, though- he’s going to get his money one way or another, and when it seems like the fate of Tom’s son is sealed, it’ll lead him to a choice that sets in motion the rest of the film, and seem to assure him of getting paid.

On the other side, we have the two main women in these films. As Kate Mullen, Rene Russo is given a simple job of being believable as Mel Gibson’s wife, and to be scared for her son. Thankfully, the screenplay eventually gives her more to do than that. As Tom’s behavior gets more questionable, Kate becomes more assertive next to him. When she disagrees with his decision to not pay the ransom, her thoughts are with her son, regardless of how Tom feels about it or tries to convince her of the rightness of his actions. When Tom has made it to where she is unable to get access to the money necessary to pay the ransom herself, it forces her into a dangerous meeting that only adds to her resolve to get her son back more, so when it appears he’s been killed, her first reaction towards Tom is anger before moving back to the role of the sympathetic wife and mother, grieving before being relieved. The stretch of film I’ve just outlined is one of Russo’s best performances, and makes her the heart of the movie, unflappable in the face of the ambiguity the story follows.

Marge Gunderson, the immortal character played by Frances McDormand in her first Oscar-winning role, is unflappable, as well. She’s also the moral compass of “Fargo.” Few characters in movie history are as genuinely good as Marge is. Good in their heart, good in her job, and good at keeping their cool in any situation, whether it’s an awkward meeting with a high school classmate over lunch or interviewing Jerry or faced with a body being shoved into a woodchipper. In reality, we would be hesitant over someone like Marge, who’s many months pregnant in the film, getting so deep into a case like this, especially when we see the amoral ways that Carl and Gaear and Jerry have behaved in this film. And yet, we believe that she would be able to not just survive this, but succeed in solving the case. She nails her initial assessment of the first crime scene along the road, all while thinking, “I need to get some nightcrawlers for my husband.” She isn’t a dutiful wife but a loving wife, and a driven breadwinner, and she earns the night’s sleep she will get at the end with Norm, and she couldn’t be prouder that his mallard is going to be on the $.03 stamp. She gives us hope that, when faced with challenges and evil behavior, we can hold on to our basic humanity in the face of it, even if it isn’t a clean happy ending like it is in “Ransom.” That’s why, for all their similarities, “Fargo” is one of the all-time greats, and “Ransom” is simply a successful studio thriller.

In the end, however, it’s worth looking at these movies next to one another, and worth revisiting them in general. On the one hand, we have two of the most idiosyncratic filmmakers of our time working at the height of their powers, and getting great work out of some of the best collaborators in the business such as cinematographer Roger Deakins and composer Carter Burwell. On the other hand, we get an out-of-character effort from one of the most reliable studio directors in the business, and one that pointed to later films that further led him out of his comfort zone, and into a new one, scored with a conventional thriller score by long-time collaborator James Horner, with some gritty instrumental pieces by Billy Corgan, and shot with a sharp eye for darkness by a previous Oscar nominee (Piotr Sobocinski) that paved the way for the rest of his career, and given a sharp edge of a screenplay by one of the most popular hard-boiled scribes of the time (Richard Price). More than their technical attributes, however, it’s their narrative ideas that make them memorable, even if their approaches could not be more different.

This is just the beginning of an exploration into the 1996 movie year for me. As the year goes on, I’ll be looking at more films from this year, and what makes this one of the most notable movie years of the 1990s.

Viva La Resistance!

Brian Skutle

www.sonic-cinema.com